Topics

- Article

- Cycling

- Member Stories

Physiological Data of Winning a 1,000-Mile Bikepack Race in Under 5 Days

The strain, sleep, and recovery (or lack thereof) from Ted King's record-setting victory at the Arkansas High Country Race.

Earlier this month, pro cyclist Ted King set a new course record in winning the 1,000-mile Arkansas High Country Race with a time of 4 days, 20 hours and 51 minutes. The race began on Saturday, October 31 at 7:30 am, and after riding over a thousand miles on and off road (with more than 80,000 feet of climbing) through the backcountry of Arkansas, Ted crossed the finish line at 2:21 am on Thursday, November 4. In order to accomplish this feat, he spent 17-20 hours per day on the bike, and only slept for a total of 17 hours. Why? “I’d never done anything like this before,” Ted said. “The opportunity to try a whole new challenge, and to do so safely - given the inherent socially distanced nature of bikepacking - was something that really made me excited.” Initially his goal was just to “finish and survive,” but as the race progressed he realized that victory (and beating a record set by a duo, no less) was well within his reach.

Challenges of Ultra-Endurance Bikepack Racing

Simply put, bikepacking is what you get when you combine long-distance cycling (on or off road) with camping. “You have to be completely self-sufficient in the middle of nowhere,” Ted explained, and have everything you need for the race with you on the bike. “It took a lot of homework,” he added, noting the time he spent researching on Google Maps and making phone calls to find out where along the way he could eat, sleep and grab an occasional shower. “It’s not necessarily the most hygienic thing, because you’re carrying as little as possible and you don’t have a change of clothes.” Over the course of the 4+ nights he was racing, Ted slept briefly in a hotel, a community center, and various places along the side of the road.

“One night I was just so exhausted that I pulled over on a dirt road in the middle of the woods, set up a bivy sleeping bag and slept right there,” he said. “It got super cold at night, dropping down from the 30s to the high 20s. In my bag I had a down jacket, winter hat and a camping stove. Not everybody carries a stove, it’s an extra pound-and-a-half, but a friend of mine who does these races a lot told me ‘The one thing you want in the morning is a hot cup of coffee.’ He’s right, but unfortunately I woke up so cold I had to get moving right away, I didn’t have time to stand around and make coffee.”

How Much to Sleep?

The Arkansas High Country Race doesn’t have stages--there are no daily starts and stops as Ted was accustomed to from his pro career competing in the world’s top events like the Tour de France or Giro d’Italia. Every minute spent off the bike is one more minute delaying you from crossing the finish line. Since this was Ted’s first venture into the sport of bikepack racing, he was unsure how to best manage his time. “That’s what showed my novice card,” he said. “You’re going to cover more distance moving than you are sleeping, and it’s your own personal algorithm on how little sleep you can actually operate on.” For Ted, that was an average of about 3.5 hours per night.

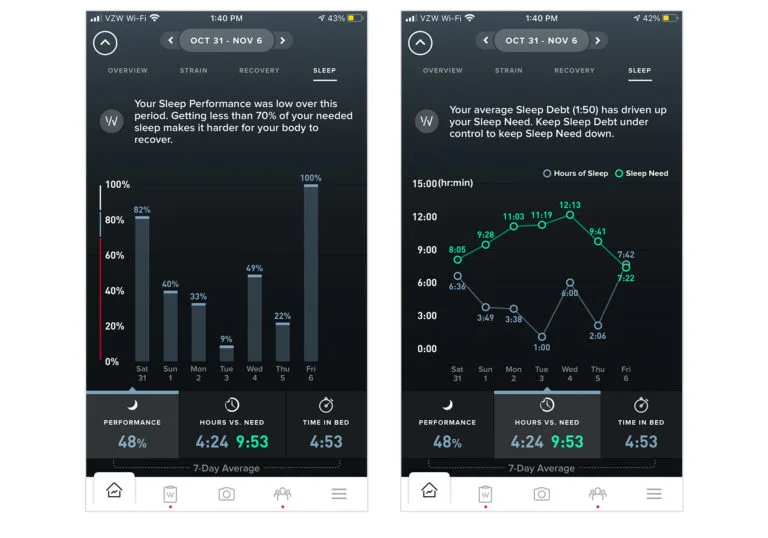

Ted King’s nightly sleep performance data and time asleep vs. sleep need, before, during and after the Arkansas High Country Race.

Strain and Heart Rate Data

It’s one thing to try to get by on just a small percentage of the sleep you need for 5 straight nights, but an entirely different obstacle to simultaneously push your body to the max every day as well. Ted’s WHOOP strain (a measure of cardiovascular exertion on a scale of 0-21) exceeded 20 each day of the race, including 4 consecutive 20.7s.

After riding 240 miles and posting a 20.7 strain on the first day, Ted slept just 3:49 and awoke Sunday with a 10% recovery (how prepared your body is to perform, from 0-100%). “A shock to my system,” he called it. Following a second 20.7 day strain and another sub-4-hour sleep, he was actually 44% recovered on Monday, saying “My body had already started to adjust to sustaining that output.” Below is Ted’s heart rate data for the third day of the race, “Fairly par for the course,” he called it. “Sleep very little (3:37 and only 33% of sleep need), wake up and ride with sporadic breaks to stop, refuel, stretch and continue on my merry way.” You can see his HR rarely dips below 120 for roughly 16 straight hours.

Fighting to the Finish

After a predictable dip in heart rate variability when the race began (from 103 to 68 to 33), Ted’s HRV actually rose significantly towards the finish. In his words, “From what I gather, that’s the chronic effect of being at that high-endurance limit for days on end. I’m not recovered, I’m so completely smashed, my heart just found a new level of always being sluggish.” Per our VP of Data Science and Research Emily Capodilupo, “That can happen in those types of situations, your sympathetic system crashes so you get high HRV for the ‘wrong’ reason.” Following a 6-hour sleep on what Ted thought would be his final night of the race, his last day of riding proved more difficult than expected. Knowing he wanted to break the record, he pushed on, “all day Wednesday into the wee hours Thursday morning. I took a pair of 15-minute naps in the final 4 hours, basically I just pulled off the road for a quick micro recharge.”

Closing in on the finish line in Fayetteville Town Square at 2:20 am.

Post-Race Recovery (or Lack of)

“I still don’t have much feeling in my fingers and very limited strength in my hands, which is as frustrating as it is scary. I’m working with some physical therapists and medical professionals to crack that code, but it seems that this is fairly standard in bikepacking,” Ted noted almost a week after the race concluded. Not from the cold specifically, but from “pinched, aggravated nerves after being on the bike for so long.” Two weeks afterwards, his recoveries still hadn’t returned to normal. “Even with relatively low exertion the past 10 days, I’m still in the yellow and red,” Ted pointed out. “A sign that I’m still destroyed from what I put my body through.”

Also worth mentioning, Ted’s in-race fueling probably didn’t do much for his long-term recovery. Given the nature of the race, his body needed quick bursts of energy however it could get them. Notable items included Reese's Pieces, diner eggs and hashbrowns, a Quarter Pounder with cheese and Werther’s Original candies. “You're not really eating the right food when you’re getting it at a gas station,” he joked. Photo Credits: Kai Caddy, @kaicaddy on Instagram Watch: Ted King - Know Yourself with WHOOP