Topics

- Article

Training for a 100-Mile Race

What does it take to run 100 miles through the Wasatch Mountains? Ultra runner Robert Edminster incorporates a wide variety of wearable technology into his training, but WHOOP is the tool he relies on most.

Robert Edminster has his dogs to thank for helping him find his passion. “I started adopting dogs and I needed to tire them out somehow,” Edminster told us. “I began jogging with them in the mountains and that quickly turned into me doing trail running.” Edminster is a site reliability engineer at a company based in Salt Lake City, Utah. He and his wife, Larissa, live in nearby Holladay, just south of the city. A key part of his training is the easy access to over a thousand miles of mountain trails within a short distance of his home. “If I want to get in 16-20 miles a day, I typically wake up and do a slow and easy 6-8 mile run before work with my dogs, then right after work I do another 10-12 miles on the trails,” Edminster said. “This summer, I pretty much gave up everything else outside of work and training. Luckily my wife runs too, it’s kind of a family activity.” Last month, Edminster competed in the Wasatch Front 100-Mile Endurance Run, widely considered one of the most difficult ultra races in the United States. Its slogan reads “100 miles of heaven and hell,” and the race features “a cumulative elevation gain of approximately 24,000 feet, as well as a cumulative loss of approximately 23,300 feet throughout the course.” The 32-year-old Edminster finished third overall (with a time of 22 hours and 55 minutes), despite the fact that it was his first-ever 100-miler. Even more impressive may be the fact that he only started running seriously three years ago.

“I’m a bit of a data nerd.”

In 2015, Edminster joined a local running club called the Wasatch Mountain Wranglers. Soon after, he was convinced that he should try competing in an ultra. “I ran my first 50k last fall,” Edminster said. “Due to the field being pretty small, I somehow managed to win it. At that point, I started to think about serious training and how I could extract the best performance from myself. This led to me playing around with a wide variety of training products. I’m a bit of a data nerd, that’s half the fun for me.”

Edminster uses each of the following pieces of wearable tech:

- A sensor on the laces of his shoe to quantify power output, which he finds useful when running up hill.

- A sleeve on his calf muscle to measure his lactate acid threshold so he can “recalibrate zones every month or so.” It also allows him to gauge muscle oxygen levels when doing interval training in order to optimize his recovery time between intervals.

- A chest strap heart rate monitor, which he says gives the most accurate readings during intense exercise.

- A clip on the back of his shorts for monitoring running form to try and improve efficiency. Edminster only wears this when he runs on roads and mentioned that he “has doubts about this product at the moment.”

- An app for tracking his runs which “lacks any real training tools and is more of a social media platform for running.”

- A multi-sport GPS watch that “sort of just ties everything together.” Edminster said that it has recovery and training metrics, but he “finds them to be so far off that they are worthless.”

Along with everything listed above, Edminster also wears a WHOOP Strap 2.0: “Of all the gadgets and tools I use, WHOOP is probably the most critical component.”

Training for the Wasatch 100

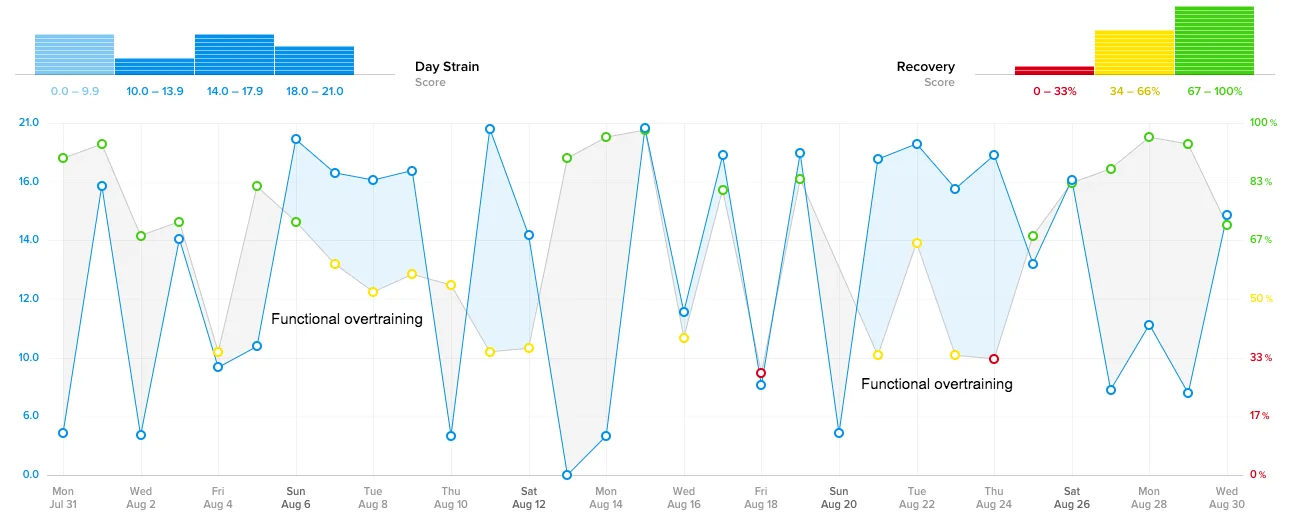

Around the time Edminster decided to take up ultrarunning, he read a book called 80/20 Running by Matt Fitzgerald. “His ideas resonated with me, so I started trying to train off of an 80/20 program–80% easy and 20% hard for a given week, Edminster said. “It quickly became apparent to me that to maximize the plan I really needed to be monitoring sleep so I’d be able to give it my all on hard work days. That’s what originally led to me getting a WHOOP Strap, but as it turned out, I based my entire year’s training off of it.” Last February, Edminster learned that he’d qualified for the Wasatch 100 in September. “I started to panic that I was actually going to have run 100 miles and there was no way I would be ready in time,” he said. “So I went all in and upped my mileage to a base of 60 per week [from about 30 per week previously] and 12,000-20,000 feet of climbing. The initial ramp up was pretty rough, but by watching my daily Strain and picking which days to go hard and which days I needed to rest, I was quickly able to get to the point that it felt normal. From there, I did much more intense training weeks where I pushed my milage to 100 per week. The only way that was possible was by listening to my WHOOP. It helped me build up to longer sleeps and maximize my Recovery for days with difficult workouts scheduled.” As the race approached, Edminster planned a pair of extremely strenuous weeks (100+ miles while climbing over 20,000 feet) where he intentionally ignored his Strain and Recovery. Look below at the four-day periods from August 6-9 and 21-24:

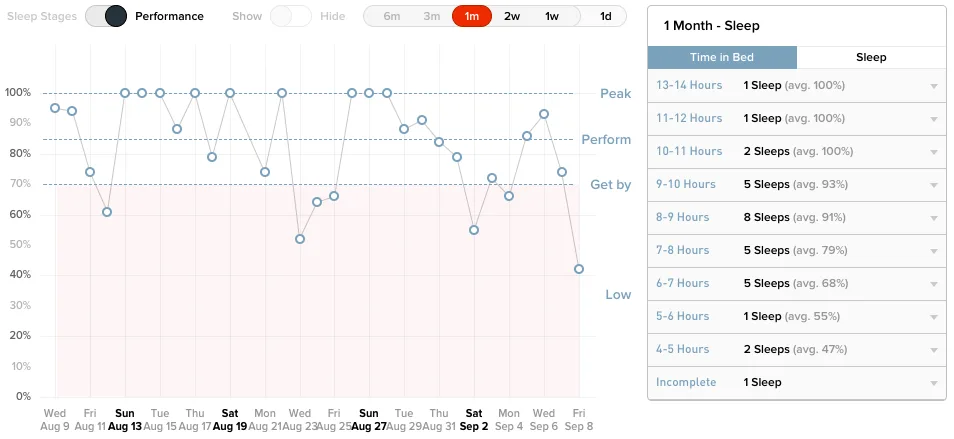

During those times, Edmister said his Sleep data took center stage: “I leaned heavily on the Sleep Planner to give me a sense of just how much sleep I needed to be properly recovered under those conditions–it was often around 12 hours. I also noticed that after each intense week, within a few days I saw moderate improvements in my HRV [heart rate variability] and RHR [resting heart rate]. This cycle made me think that a short period of overreach once a month or so might be beneficial for making large gains throughout the year.” “When race day [September 8] drew near, I started to taper,” Edminster explained. “It’s not easy to go from always working so hard to backing off and doing barely anything for a couple weeks. But that’s what you have to do to be ready to run 100 miles. I focussed on getting as much sleep as possible. The night before the race, I was so excited I could hardly sleep. But I wasn’t too stressed about it, because I knew I’d gotten great rest the preceding days.”

Edminster slept only 3 hours and 45 minutes the eve of the race (he was in bed for 4:54 and woke up at 2:57 am). However, he averaged 7:33 per night for the month prior, good for an average Sleep Performance of 84%.

What is it like to actually run 100 miles?

The Wasatch Ultra Marathon began Friday, September 8, at 5 am. To finish, runners were required to complete the course within 36 hours, by Saturday at 5 pm. Edminster’s average pace was 13:45 per mile for the 100 miles. He crossed the finish line in third place at 3:55 am Saturday morning, 22 hours and 55 minutes after he started. “Ultra’s are crazy, but you don’t go all out the whole time like you would in a normal race,” Edminster said. “The only way to do it is to slow your heart rate down. Mentally they can be really hard to keep going, especially through the night. Some people do take naps, that’s not unheard of. But if you’re near the front you’re not napping, the energy and adrenaline keeps you going.” There are also many other significant challenges to overcome beyond just the sheer length of the race. These include unfriendly rocky terrain, thin air at high altitudes and brutal temperature changes ranging from 90 degrees in the valley during the day, to the upper 30’s in the mountains at night.

“A lot of thought and preparation has to go into what you wear and bring,” Edminster said. “I filled my living room floor the day before the race with all the gear I might need–a headlamp for night time, fresh clothes, tights and waterproof clothing for unexpected showers, etc. You also have to take into account things like ‘at what time of day do I need to stop dumping water on myself so I can dry off and stay warm later?’” Most of the course consists of trails, with some steep enough that hiking is necessary. Edminster stated that a common strategy is not to run uphill: “The speed that you gain over hiking is not worth the effort, these races are usually won on the downhills and the flats.” There is some occasional road running as well, not to mention a few unexpected obstacles along the way. “At one point in the night I had to navigate through a pretty big field of cows,” Edminster joked. “There were a lot of calves, I was nervous I might upset one of their mothers.” Luckily, the runners don’t have to carry all of their gear with them for the entire race. They can place drop bags along the way–Edminster noted a change of clothes at the 65-mile mark. As with any race, there are also aid stations set up throughout the course. However, they go well above and beyond what one might expect: “They are typically spread out every 5-10 miles. They’re really well stocked, most made quesadillas and burritos along with a standard assortment of energy bars and candy. Volunteers that run the aid stations choose what food and other random amenities they provide. Many of them get really into it. I remember seeing a cowboy theme, a nurse and doctor theme, even . One was Swan Lake themed and had a kiddie pool for us to cool off in.”

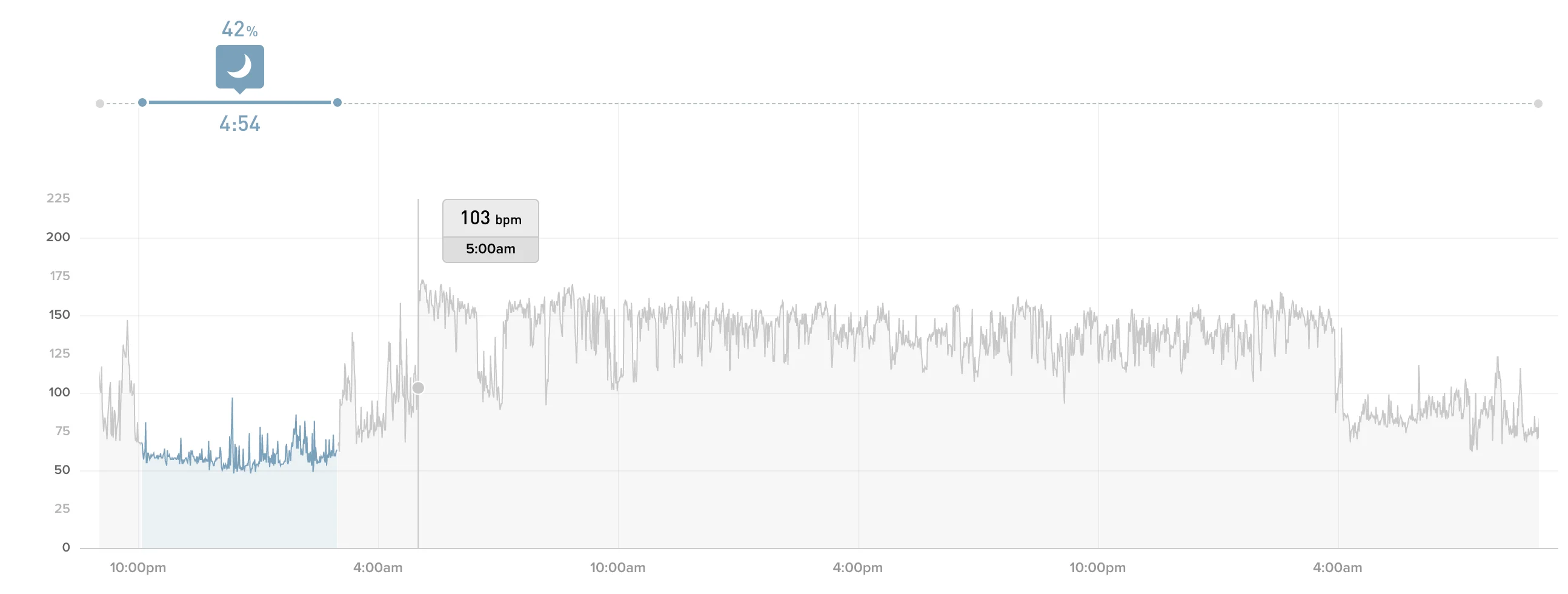

Edminster called lying in the pool “the turning point” of the race for him. It was around 2 pm, during the hottest time of day. “Not many people took advantage of it,” he said. “I actually tried to convince a few others that I saw sitting and puking to get into the pool to cool down. About 50-60 runners dropped out at that point due to heat exposure.” Of the nearly 23 hours Edminster spent on the course, he said only about four of them were uncomfortable. For the other 19, he “loved every second of it,” enjoying the mountains and the sights. “I went out much too fast early on to stay with the leaders. After an hour-and-a-half I backed way off to recover. After that I made a more measured attempt at moving my way up towards the front.” Below is Edminster’s heart rate data for the entire day. You can see it spiked as the race began, then dropped dramatically for a period of time just after 6:30 am when he realized he needed to rest. From there, it stayed consistently elevated for the next 21 hours:

“I didn’t go into the Wasatch 100 thinking I would do any better than finish,” Edminster admitted. “But through well-informed training and smart racing, I surprised myself and pretty much everyone in the local running community.”

Why he’s now hooked on WHOOP

“In the ultra community, people constantly warn you about overtraining,” Edminster said. “I’ve seen many of my friends go through it–workouts that would normally take them a day to recover from suddenly take a week. It’s really common in our sport because of the massive volume of training you have to do. WHOOP is somewhat of a silver bullet in helping me catch that and see the early warnings signs. Having data to back up my decisions of when to go and when not to go helps me avoid that pitfall.” “When you’re training that much, one of the things that’s easy to skip is sleep,” Edminster added. “I never paid much attention to that before. Having a visual indicator of it is huge, as is seeing the resulting dips in my HRV after not >sleeping and recovering enough. Prior to having Recovery data, I didn’t really know when I needed rest. Even if I felt like I did, I’d assume I was just being lazy. WHOOP takes the sting out of the ‘you’re just not working hard enough’ thought process that goes into taking a rest day.” Edminster also finds the Day Strain metric extremely useful: “WHOOP does a great job of quantifying everything else in my day beyond just my workouts, and how it all compounds. It’s always interesting to see the Strain from my work events and how much they affect my body compared to traditional athletic stuff. For example, major product releases at work have made me alter my training to accommodate for the additional Strain. By understanding everything my body goes through on any given day, and the effect that will have on the following days, I’m able to adjust my workouts to maximize when I am well recovered.” “I am constantly telling fellow ultra runners how WHOOP has helped me optimize my training,” Edminster concluded. “I haven’t taken my Strap off in six months.